Keller Crafted & Big Picture Beef: The Grass is Greener on the Carbon Side

(March 13, 2019 – Interview by Cirina Catania, Senior Editor, USTimes.biz) Wander through the grocery store, head to the meat counter and you’ll see numerous packages that herald “Grass Fed Beef.” Is all this beef really grass fed? Probably, as most beef is grass fed for part of their lives, but the question to ask is, “Is this beef grass fed and grass finished.” In that case, most of the meat you see on those shelves has lived the last months of their lives crammed in a stockyard being fed grain and injected with hormones and antibiotics.

Not only does that bother us as we love animals,

Additionally, wouldn’t we want to support our local farmers who work tirelessly to raise food for us? Much of that meat is not accurately labeled with its origin. In fact, much of our meat comes from South America or Australia, countries where organic farming is not as closely regulated as it is in the United States.

In our quest for truth and a desire to become healthier all while enjoying great tasting food, we decided to interview two experts on the subject, Mark Keller, of Keller Crafted Meats http://KellerCrafted.com and Ridge Shinn of Big Picture Beef http://BigPictureBeef.com

For those who prefer reading, here is the entire transcript of my interview with Mark Keller and Ridge Shinn:

Cirina Catania: (00:00) This is Cirina Catania with US Times. I am very fortunate today. I have two amazing experts on the line with me. I have Ridge Shinn who is the Founder and CEO of Big Picture Beef (BigPictureBeef.com) and he’s a leader in this thankful shift away from feedlot beef to 100% grass fed and grass finished beef. In other words, no corn ever. And I’m going to be asking him during this interview, why on Earth did Time Magazine call him a carbon cowboy. That’s fascinating to me.

Cirina Catania: (00:31) And Mark Keller, you’re here as well. The Founder and CEO of Keller Crafted Meats at KellerCrafted.com. Mark works

Cirina Catania: (00:55) So I don’t even know where to start with the two of you, but why don’t I just ask you how did you meet each other and what’s the history there? Can you tell us?

Mark Keller: (01:03) This is Mark and I’ll jump in first. So I think it was in ’99 I started reading the Stockman Grass Farmer, my favorite periodical to this day, which focuses on grassland farming and regenerative agriculture. And I was introduced to Ridge just through reading and then through going to the annual seminars. In 2006, maybe 2005, I was in pursuit of getting some heritage hogs and he helped me talk it

Mark Keller: (02:25) Every time I talk to Ridge, it turns into this

Cirina Catania: (03:00) Ridge, what do you have to say about what Mark just said?

Ridge Shinn: (03:03) I remember some of the things a little bit differently ’cause I think that actually the fabulous editor of the Stockman Grass Farmer who’s now deceased, Al Nation, was

Ridge Shinn: (04:05) And so he called Mark and me and a number of others, and we developed that white paper which was the genesis of that project. They didn’t follow all of our advice of course, but they took a bunch of it. It was a very interesting project. So we worked quite closely on that. And you know, I was excited to hear what Mark’s got going out there. I think this business is exciting because the market is so vast that the competition is insignificant. If you think about it, you know, the market for regular beef is about 100 billion dollars, and grass fed beef’s about four or five billion and is slated to grow to 30 billion. So who of us can be competitive in that race? There’s plenty of room for all of us to play. And what’s exciting is the people in this field that I know, we’re all on a very steep learning curve, which is exciting, which is one of the reasons that we love doing it. But the more we can share and collaborate, the faster we go.

Ridge Shinn: (05:13) I mean, there’s nobody that’s going to take this business. One of the big four meat companies tries to do it, which they are trying, but they just don’t get it, and they’ll never get it right. They’re not really competition. But the more we can collaborate, the better.

Cirina Catania: (05:29) There’s a big difference between being in the business to make lots of money and being in the business because you want to honor the animals and feed people

Ridge Shinn: (05:39 ) Precisely, precisely.

Cirina Catania: (05:40) Ridge, you’re in Massachusetts on the East Coast and Mark, you’re in Northern California on the West Coast. And it’s interesting to me that there’s this really energetic movement that is happening now and you are in the process of helping farmers learn how to do this new way of raising grass finished beef. And we’ll get into that in detail. But can I just ask you, and this was one of the main reasons I wanted to do this, you walk in the store as a consumer and you see grass fed, grass fed, grass fed everywhere on the labels. And I think a lot of people don’t understand that there’s a big difference between grass fed and grass finished. There’s starting to be a bit more education out there, but can I ask the two of you to explain to our listeners the difference.

Ridge Shinn: (06:28) Sure.

Mark Keller: (06:29) Sure. I appreciate the question. Grass fed and grass finished beef has gotten a lot of interest, and rightfully so. Grass fed in this country right now, according to a couple of studies that I’ve looked at is, at least 75-80% of the total tonnage that’s being consumed is imported from anywhere from outside, usually South America, and then Australia and New Zealand. So there isn’t a lot of domestic product being consumed of the grass fed.

Mark Keller: (07:03) And then there’s the grass finished which is the quality part, which actually means grass fattened which really displays the art as a combination of genetics of the farming practices that the farmers deploy, the grass finishers deploy, and the stewardship of those animals all the way from when they’re next to their mother’s side through weaning, all the way through to a perfect animal that is going to be nutrient dense and full of fat. There’s probably a few listeners out there that are looking for grass fed beef because it’s leaner, and I would like to try to urge the listeners to think about where does all of the good stuff come from, because it’s my understanding that the more fat, the more goodness, the more taste, the more flavor. So it’s like eating that ripe tomato on Forth of July or during summer time in your garden and you just go, “Oh my gosh, it tastes amazing.” Well, there’s also more stuff in it, more total dissolved solids in that tomato, and that’s all of our indicators that we’re eating nutrient dense foods.

Mark Keller: (08:11) And so goes with grass finished beef.

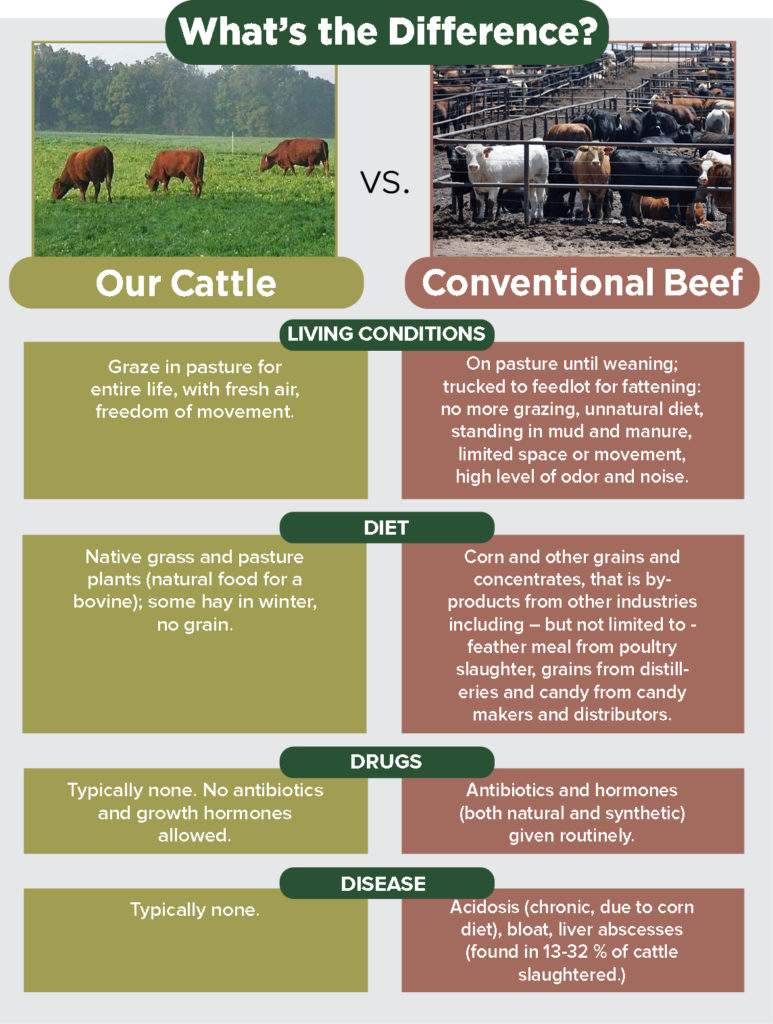

Cirina Catania: (08:23) I’d like to paint a picture for people and talk about the difference between the cattle that you both work with and what we’re going to call conventional beef, like their living conditions, their diet, what drugs have they been given, and then we can also talk about disease if you want. But can we start with the living conditions, and be very specific about that if you would.

Ridge Shinn: (08:44) Sure, yes. And back to the definition of grass fed and grass finished, all cattle are grass fed. So all cattle, at least in the US, are raised on grass because it’s the cheapest way to raise cattle. So when a cow as a calf, she’s typically eating grass. She’s not being fed grain, she’s eating grass. And she raises that calf for a good part of its life. And then maybe the calf is weaned and then it’s backgrounded again on grass because it’s the cheap form of production.

Ridge Shinn: (09:15) Where the whole thing changes

Ridge Shinn: (10:02) Yeah, so you have all these conditions that are magnified by putting them into the feedlot. It changes the fats in the meat from a perfect balance for human health to one that’s kind of out of whack for human health. E. Coli’s an issue in the feedlot situation as well. And we can dig into all those things. But grass finishing is when the animal then, instead of going to a feed lot, goes to a grass finishing plant which is a large farm with larger grass. And the big difference in the finishing is … The challenge of putting fat on a bovine is to provide it with energy. That’s why the corn is used, because it’s got lots of energy. It’s cheap and fast. But harvesting the energy in the grass is the real art to finishing. Everybody thinks that grass is grass and they think a cow is a mowing machine walking around going moo, mowing machine. But the cows are very selective. And when the cow is growing the calf, she doesn’t need much because she’s just maintaining her body weight, and her body takes the grass and converts it to milk, this magic that makes the calf grow. And then the calf has to grow its long bones, so it can do that on a lot of protein, which is in the grass.

Ridge Shinn: (11:13) But when we get to

Ridge Shinn: (11:44) But the [inaudible 00:11:45] in grass finishing is to optimize that available energy in the grass for that finishing out. And that’s the art, and that’s what makes them finish in a reasonable amount of time efficiently. It still takes longer than finishing on grain, because the grain is very concentrated in energy. And in reality, they do it to an extreme on the feed lot.

Cirina Catania: (12:07) So Mark, at what point do we leave the initial stage and move into what I’m calling the fattening stage and how far do they get there?

Mark Keller: (12:18) In our program, our Lost Coast program, the calves, whether they be steers or heifers, they are going to be finishing starting at around 1,000 pounds, going up to our ideal harvest weight is about 1,250 pounds on a live weight basis. That makes, for our genetics, which are mainly Angus, Hereford, and

Cirina Catania: (12:54) Talk to me about the salad bar. You used the term “salad bar” when I was talking to you recently. What do you mean by that for the animals?

Mark Keller: (13:00) I talk about the salad bar as being a diversity of different feeds and stuff that might be found in a pasture. The animals will select, you know, whether a plant might be high in protein or might be high in energy as Ridge was eluding to, based on their needs. And some of these grasses that are very sweet are very high in energy, and that’s what we’re looking for for finishing. We do some

Mark Keller: (13:43) But there’s a diversity of plants out in the pasture and they all deliver a different cocktail of nutrition, basically.

Ridge Shinn: (13:51) Right. I just want to concur with Mark’s comment that the cattle are extremely selective. And really, they don’t have a tough set of teeth. So like a horse will go in and he can eat the grass, bite it off, what the cows do is swing its tongue out and kind of grab it and bring it in and break it off. And what is remarkable when you stand back and you watch cattle graze, they are incredibly selective. They want this and this and this. And actually, there’s some research that’s been done at Utah State that was fascinating because what they did is, these were cattle they were feeding in the barn and they would feed them more protein and less protein. And then they had three

Ridge Shinn: (14:59) But the more diverse, the more choices there are, and there’s a lot of things that they will eat with relish like a plant like

Cirina Catania: (15:21) Are the grasses very different on your different sides of the country?

Ridge Shinn: (15:26) I would say from my experience in California, which was up north up in Santa Margarita near San Luis Obispo, very different and very different management. See, there, at least on those ranches, it rained once a year basically, and it didn’t rain all summer long. So basically you had one shot at that grass. And the grass looked dry and peaked, but it was incredibly high in breadth and great at fattening cattle. Now back here with our tremendous amount of rain, we get different species, you know, lusher species that we can graze and come back to it in 40, 50 days, very quickly. And that’s where we’re very different on the two coasts. They’re quite different. And probably species. Our native species tend to be orchard grass and red clover. That’s what comes in eventually, with some forbs. But the rain is

Cirina Catania: (16:23) Right. I was just going to ask Mark. The climate in the area you call the Lost Coast is near the ocean. What kind of grasses are grown there and how does that climate affect what the animals eat?

Mark Keller: (16:35) Yes. Ridge was absolutely right with the assessment of central coast and a lot of California. The Lost Coast program, I really honed in on this area that’s close to the ocean, very moderate in temperature. There’s not a lot of swings in terms of temperature. It’s very moderate all the time because it is close to the ocean with the big thermal mass there of the ocean being more or less about 52 degrees or so. They don’t have very warm days and don’t have very cool nights. Makes for great growing conditions.

Mark Keller: (17:07) Also, there is a lot of precipitation just coming off the coast in the form of fog and then also nice rainfall up in that part of the country. So this is on the northwestern part of, tippy top part of California. It’s paradise for cows, it is cow country, and for growing high octane feed. Our feed here, our annual and perineal rye grass is our source of energy, and then white clover is the main source of protein here.

Mark Keller: (17:47) The whole purpose of setting up this

Cirina Catania: (18:19) I want to ask you guys about the term “sustainable” and about the term “regenerative ag” and how does that apply to the way you live your lives and the way you work with your farmers? Because those are subjects that are very, very important to all of us out here in the world right now. Who wants to start?

Ridge Shinn: (18:37) Well I can start. The terms “sustainable” and “regenerative,” sustainable is kind of like good. It’s better than destruction. It’s just kind of like a maintenance term, vs. regenerative really embraces actually building in the process. And in terms of what we’re doing with the

Ridge Shinn: (19:48) I mean, it’s like one of those impossible things to really consider that you actually can build soil and wealth and carbon while you’re harvesting protein. It all goes back eventually to photosynthesis and how you manage the grass as the solo collector, which just by its nature will take that carbon, that CO2 out of the air and transform it and put it down below the soil in a stable form. So you’re building wealth while you’re producing phenomenal meat. I mean, it’s like a win-win. And that’s really what we mean by “regenerative.” It’s much more than sustainable. It’s like a whole step up.

Cirina Catania: (20:28) So would you say then that the people that are critical of the meat industry and the cattle industry, when they say that the cows are ruining the land, are wrong?

Ridge Shinn: (20:38) No, they’re right for the vast majority of the way cattle are raised. So you know, if you turn cattle out in a big area and just let them graze and don’t move them like the buffalo, every time a new plant grows up, they’ll go over and nip it off. And eventually that kills the roots and eventually you turn that land into a weed patch or a desert, depending on the environment that you’re in. That’s what happened. That’s how most cattle are raised. So they’re not wrong. And that form or production is very destructive to the environment, to the water systems, to the whole thing. And what we’re doing instead with the capturing carbon, we capture water, and it’s a very different system.

Ridge Shinn: (21:20) But at the same time, red meat is vilified as the cause of climate change, but what we’re finding is that the cows

Mark Keller: (22:31) I’d like to jump in on this because really why I really wanted to have this dialogue because this is incredibly nuanced. And the conversations that are being had on a generalized level is like throwing the baby out with the bath water. And in fact, in this case, for the sake of our planet, I’ll just throw it out there, it’s really important that we don’t vilify the thing that probably has the greatest potential to help our climate. And I know

Mark Keller: (23:44) So there’s a conversation, and what I just don’t want people to miss, what Ridge just said, that they’re mainly right. But you can’t just throw the baby out with the bath water like I just said. There is a way. There is a path forward. It’s not common, but it’s time to embrace kind of new technology, a new way of asking for the right type of products. ‘Cause when you ask for it, it’s uncanny how human beings learn how to produce it. You know, when there’s a market, don’t worry, they’ll figure it out. But when people are confused about what they want, and they don’t understand the difference, they won’t ask for the right question.

Ridge Shinn: (24:18) Yeah, I couldn’t agree with Mark more. You have to figure out the right kind of beef. What Mark is saying is it’s very nuanced. So you can get 100% grass-fed beef that was raised in Australia on the range in the worst possible management conditions. It never ate any corn so it can be certified 100%, but it was destructive to the land that it grazed on. Very different than cattle that are actually finished and rotated and in a system where the system is actually sequestering carbon while the beef is being raised. And that right now is a very small percentage of the beef being raised. But if the customers could understand it and embrace it and pull on the rope and demand it, I mean, we would literally, we could put all those prairie lands that are in harms way back into grass, because the money would be there. And that would definitely, it would change flooding in the Mississippi, it would change the weather in the west, and

Ridge Shinn: (25:30) So it’s a very possibly optimistic outcome. But cattle are critical. The cattle are critical to the paradigm. They are what makes it happen fast so we can make these changes to a dead piece of land and in three to five years, we can bring it back into verdant prairie. We’ve done this all over the country so we know it works. And that’s what’s very optimistic and exciting about this, is that this change could happen very quickly.

Cirina Catania: (25:57) Here’s what excites me about this, is I’m all for, and I believe everybody is all for creating healthy soil ecosystems, correct? And also we’re all for this slow food movement that’s been happening in the last, I don’t know 10, 15 years, slowly gaining momentum and creating some prosperity for our rural economies. I think both of you work with rural farmers, am I right?

Ridge Shinn: (26:22) Oh yeah.

Mark Keller: (26:23) Absolutely. Those are the only people I work with.

Ridge Shinn: (26:26) What it is is farmers as much as a lot of people think that oh, the dumb farmer, the farmer’s incredibly smart and they are very good at trying to figure out what to do. And what I think is remarkable is that the ones I’ve worked with, farmers and ranchers, are so closely aligned to the customers in the city who are interested in the environment, interested in their family, interested in

Ridge Shinn: (27:12) You know, a lot of people vilify now the farmer, but I mean, the farmers are desperate. Corn and soy farmers are committing suicide. Dairy farmers are committing suicide at almost twice the rate of vets returning from combat. I mean, it’s a very sad situation, and they’ve been put out of business by our food system, and they’re desperate. They’re looking for a way out, and to throw them a lifeline with this new methodology. I mean, they’re going to be all over it. They really are. That’s what excites me is it’s like a way out of this spot that monoculture industrial agriculture has created. And it’s something that can happen quickly in terms of it’s not going to take eons to put that carbon back in the soil again. It can happen in 10 years. You know, we can put down a tremendous amount of carbon in a very stable form if we could get this paradigm shift going on both side, both the customer and the farmer. But it’s just there to be done.

Cirina Catania: (28:13) The consumer always wants to know about pricing and there’s a lot of beef out there that people can buy for a lot less than what it costs to raise really nutrient dense,

Ridge Shinn: (28:33) Yeah. So when I give my talk, I talk about all the benefits, the fats and the vitamins and the health and putting carbon down. And then I always say to the crowd, so the problem is price. And there’s always like, “Yeah, price, price.” So then I flash a split slide on the screen and the slide has a picture of a Snickers bar and a pound of ground beef. And I say, “Okay,” and everybody laughs. And I say, “Wait a second. Now do the math. If you do the math on this Snicker bar, it costs you $1.27 for 1.2 ounces, so it’s actually costing 92 cents an ounce. Now look over here at my grass fed beef that’s whatever, it’s $7.99, it’s 44 cents an ounce.” I said, “You have this incredible disparity but you go and buy that Snickers bar everyday and think twice about buying my ground beef that’s half the price.” And that’s before even talking about the health benefits. But the way the industry has packaged, everything, you can look at it in cereal. It’s all kind of products where you think nothing and throw that in your shopping basket, but if you were to sit down and calculate, the beef really isn’t that expensive.

Ridge Shinn: (29:37) But it’s a big paradigm shift because the beef that’s in the meat case is less expensive and people always tell me that. “Well, if modern beef is half the price.” I said, “Yeah, but you paid the price. You paid the taxes to the IRS. They gave the money to the USDA. USDA gave a subsidy to the corn guy and soy guy. That’s the only reason they grow it is for that subsidy. Now they have so much cheap corn and soy that we feed it to animals, which actually makes them sick and creates nutrient loading of all the nutrients and pollution, and on and on. But that’s why we do it, so you actually paid for that meat. You paid the extra amount of money, but you paid it in the form of subsidies to the corn and soy guys, and nobody in that system paid for any of the externalities of the flooding and the dead soil, and other changes, and on and on.” But it’s a hard sell. But it’s a true story that that meat really isn’t cheaper.

Cirina Catania: (30:34) Also, it’s so much healthier. Mark, you talk about the benefits of bone broth. Talk about that for a minute. Even something as simple as bone broth.

Mark Keller: (30:43) Oh absolutely. It’s a staple. It’s what I fuel my own system with regularly. It’s medicine. I mean, food is medicine and we make a bone broth that’s very high in the knuckle bones and they’ve got some marrow in it as well. And I work really hard and it seems to do me really well. It just tops off my immune system. Nutrient dense, it’s really a miracle food. You know, but we’ve had plenty of customers that have these autoimmune diseases and they’ll buy grass fed beef from us. In the box, we always throw in some bone broth as well. And we just get tremendous calls, results. People that their western medicine is failing them and that eating good, real food that’s actually produced by artists, by experts. These are not just the average Joe out there. These are highly skilled technicians, these farmers, and they’re creating medicinal grade food in the form of grass fed beef. And then really my job at Keller Crafted is not to screw it up. Just do a great job with it, you know. Just take it the next mile until we pass the baton off either to the retailer or to the restaurant or wherever the … the direct to the consumer through our meat box. But anyway-

Cirina Catania: (32:05) Okay. I have a confession. We’re talking about nutrient density, right? When I eat meat, I go right to the fat. I love the fat. Can you tell us what the difference is between good an bad fat and how do we know?

Ridge Shinn: (32:20) Well, I can speak to that. You know, a lot of people vilify some of the fats and some people vilify all fat. Those people are wrong. But in terms of the fats found in beef, there are the fats that are talked about the most are omega-6 and omega-3. So omega-6 fatty acids a lot of people say omega-6 is the bad fatty acid because it’s inflammatory and this and that, and that’s a true story. In grain fed beef, you’ll have 10 omega-6 for every one omega-3. But what we find when the diet is forage only that actually the researcher at Hunts University, Susan Duckett, said it’s like a fingerprint. She can tell whether the bovine or not by looking at the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3. And in a forage finished animal, it will be 1.2 omega-6 to one omega-3. And what it turns out is both omega-6 and omega-3 are EFAs or essential fatty acids. Humans need both of them for brain function. You just need them in the right ratio for human health. And whether you have 10 omega-6s to one omega-3, then that ratio is out of whack and that causes all the things that are attributed to red meat, all the health issues that are attributed to red meat are really the grain feeding of the red meat, not the red meat itself.

Ridge Shinn: (33:46) But the fact is, and once you get that ratio right, then more fat is better and guess what, that’s where the taste is. So, you’re quite right to go to that fat if it’s 100% grass fed. Stay away from it if it’s not.

Cirina Catania: (34:01) Yeah, it’s true. Mark?

Mark Keller: (34:03) Yeah. Well, I would say my understanding of fat, and I’m with you Cirina, my wife and I, we go after the fat big time, but we are, you know, we’re pretty lean and mean. And I know Ridge is too. We eat heavy on fat. We eat, you know, full butter and everything full fat. We don’t get fat. It’s also very essential for us to avoid fats that are produced in the toxic approach because all of those toxins are going to be bound up in the fat, a lot of them, and Ridge, you can tell me if I’m wrong on this one. It’s exactly the thing you don’t want to eat if it’s being raised with all the chemicals and all the pesticides and you know, all the antibiotics and so forth. Please avoid it because that’s where it’s going to be hung up.

Ridge Shinn: (34:47) Exactly. One of the fats to highlight is

Cirina Catania: (35:24) I’m liking that.

Ridge Shinn: (35:27) All of the other places that that fat is found is in the rumen of a bovine. That’s where it’s created. So it’s fascinating when you begin to really dig in. You know, it’s one of the fatty acids, conjugated linoleic acid.

Cirina Catania: (35:41) What I’m hearing is that the consumer really needs to ask where does this beef come from, because I get inundated with emails from companies that sell meat and they’re all telling me that they’re 100% grass fed. Some of them are saying they’re grass finished. But I don’t know the origin of that meat. A lot of it’s imported, but they’re not telling me that. So how can I find out where the meat comes from? Get to know my supplier, I guess.

Ridge Shinn: (36:09) Well, to some extent that’s true. You know, in our business we feel that that’s the primary question the consumer should ask is where does it come from, because once you know that, then you have the trail that you can go and reconstruct. You might not do it, but you could do that. And so what we’re doing in our company is actually just on the cusp of buying a traceability system where we’ll have an electronic ear tag on every animal from when it’s born right until it becomes meat, and we’ll be able to communicate that information to the customer.

Ridge Shinn: (36:46) So in our case, it’s fairly complicated. So there’s a

Cirina Catania: (37:19) That’s wonderful.

Ridge Shinn: (37:20) But see, our challenge is we’re dealing with a whole bunch of different people and that’s the only way this is going to succeed at a scale is to aggregate from a whole bunch of different people. But we are very interested in communicating to the customer, the farms where it originated. We really want to co-brand all our farms and farmers and you can get some real opportunity, whereas most beef has no trail, no trail at all. Either it came from ConAgra or it came from [inaudible 00:37:51] or it came from JBS. That’s all you know. You don’t have any clue. And that’s all they want. They’d rather you don’t know.

Mark Keller: (37:59) Ridge, you know, to that point, at Keller Crafted, on every package that we produce, the farm name is on every package. And we found that focus is really the primary thing in terms of getting with and sticking with the best farmers that we can and helping them grow and scale. It just allows for that consistency of quality and deliciousness and overall results that we’re looking for in terms of the environmental and the supply change. And then also getting the product to and through the market where there is very little infrastructure. And that’s kind of the core of my business. I just wanted to farm and I realized there was no infrastructure to really farm the way I wanted to farm. And I ended up having a meat business because there was no one else to do the work, you know, and I trusted me. So I was able to start that.

Mark Keller: (38:51) But it’s so important to do what Ridge just said, to get behind these great farmers that really know what they’re doing and really you can scale. We really can. There is a big challenge ahead of us to feed a lot of people. I’m never going to come across and say that I had all the answerers, because it’s very, very complicated, but I do believe that there are some very big, bright, shining, yellow flashing lights that are saying, “warning, do not go down this path.” And then there’s green lights say, “It’s a good idea to head down this path,” you know. And I think that what Big Picture is doing and what we’ve got cooking up there with Lost Coast is the beginnings of that. I know that to be right. The question is how do we make that scale and get it to more people and have them have great opportunities.

Mark Keller: (39:39) There’s a lot of stigma around people that tried

Mark Keller: (40:48) A lot of times during the very rapid growing season, these animals are being moved every couple hours, not days, hours. New breaks. And they’re very docile. You barely have to move them. You just have to show them a new break and they walk across and there’s no hollering, there’s no dogs chasing them. There’s none of that. So when they’re being moved around or loaded into a trailer to go to the packing plant, the amount of stress, ’cause they’re used to having a good relationship with human beings, not being frightened of them all the time, they associate them with ice cream, you know. Going to the next ice cream parlor, you know. And so it makes for just a tremendous eating experience.

Ridge Shinn: (41:26) I concur.

Cirina Catania: (41:27) What do you want to leave people with today? And I’m going to ask you the same question, Ridge. What advice do you want to give people listening today about how to find healthier beef?

Mark Keller: (41:37) Cirina, that’s a really amazing question. There’s a couple of things. First one is, I want people to feel that they’re in control of some pretty powerful options with their decisions. I want people to feel hope. There’s some scary things happening out there right now with our climate change, with the way that for the second year in a row, the average life expectancy in America has gone down give all of our technology and better health care. That’s very sad and very scary, but there is hope. And what I’d like to offer is that through good nutrition and being stedfast and asking the right questions, being curious, and being skeptical, those are all good things. Those are all good things and there are people like Ridge on the east coast that are working. He’s been working tirelessly. I mean, I’ve known this guy for 20 years and he has never dropped the flag. He’s not chasing money to get this thing done. This is not a fad. This is a way that we can treat animals with extreme dignity. We can help our environment regenerate, which means we’re putting back more than we take.

Mark Keller: (42:56) So the definition of sustainable, it is that we can do something in perpetuity, which is very different from regeneration, right. So through this action, we can actually give back more than we take. That’s kind of like the opposite of business rules. No, we take more than we get. We can heal the landscape, heal rural America, we can treat animals with dignity, and we can nourish people. And to me, I see this really bright light, what Ridge has got going. He’s a huge inspiration to me. We only seek to produce the best quality food that tastes amazing. I believe it has to taste amazing or people won’t buy it. You know, that’s part of my whole culling process is farmers that can produce great tasting food. But if I had to tell people to take one thing away is, there is hope. And in this whole process, there is a lot of goodness. There’s a lot of great meals to be had with the people that you love the most. There’s a way that we can begin to look into our not so distant future. So you know, we’re looking at 30 years down the tracks here, we’re going to have a very different world with the population growth the way that it’s stacked up to come.

Mark Keller: (44:15) We need to act now. Time to act is now. It’s not later. We can’t kick the can five years down the road. We need to get educated. We need to get mobile and we need to say yes to the right things and no to the wrong things, and maybe eat a little bit less but eat better food. So that’s my long-winded answer to a short question.

Cirina Catania: (44:36) How about you Ridge? What would you like to leave people with today?

Ridge Shinn: (44:39) I’ll try to boil it into sound bytes. Save the planet, eat more grass finished beef. That was the title of that farm magazine article. And then here’s another sound byte. Beef with no regrets. A lot of people think red meat’s bad. But if you eat the right kind, it’s good and good for you.

Ridge Shinn: (44:57) And then the final one is that what we’re trying to do in our business, and this is what I really want customers to understand, we have a little motto that everybody in the food chain has to eat. So the microbes have to eat in the soil, and the grass, and the cow, and the farmer, and me as the aggregator, and the distributor, and you as a customer. Everybody has to eat. And if everybody eats, then nobody’s getting screwed. If nobody in the system’s getting screwed, if the microbes aren’t getting screwed and killed then the soil’s not getting screwed and killed, then the farmer’s not, then all of a sudden you have this righteous system which, as Mark says, is a very optimistic outlook for the future if people could understand it. It’s very complicated. It’s very complex. It’s a lot of nuance. And it’s pretty hard to sort out, especially if you have no background with a farm or a cow or any of it. And it’s very hopeful. It is extremely hopeful that we can pull that carbon out of the air quickly and have great food to feed a whole lot of people. And we actually can magnify the output of the land. This is a whole nother topic, but we can increase the biomass grass on a piece of land three fold by these methodologies. So there’s [inaudible 00:46:16] upsides in this system once we get up and running.

Cirina Catania: (46:19) Well, this is fascinating. I love the idea of in a way, going back to basics. You know, I believe that farmers are the true stewards of the land, that they can be helped to understand how to create these new ecosystems that you’re talking about, put carbon back into the soil, feed us nutrient dense food that also is absolutely delicious. So I thank both of you so much for doing this today. I am going to have you back again. In the meantime, I invite our listeners to go to BigPictureBeef.com and check out what Ridge and his team is working on there, and also check out KellerCrafted.com and Mark and his team and what they’re doing there.

Cirina Catania: I’m Cirina Catania with US Times, and thank you for listening. And remember what I always say, get up off your chair and do something wonderful today. Until we meet again, have a great night.

Mark Keller: (47:16) Thank you.

Ridge Shinn: (47:16) Thank you.

Cirina Catania: (47:16) Thank you both.

###